Exploring Jura: A Journey Through Domaine Labet

Geography, Unique Terroirs, and Diverse Wines of Jura with an Inside Look at Domaine Labet

It's hard to believe, but here I am at Domaine Labet! Thanks to Snezha and Vasya, my close wine friends, for making this possible, and to Charline Labet for her warm hospitality. Despite her busy schedule and the demands of her two adorable children, Charline dedicated over three hours to showing us around the winery and cellar, both seamlessly integrated with the home where this dedicated family lives and crafts their wines.

This was my first time in Jura, so before diving into my visit impressions, I prepared a brief snapshot of the region for my own recap, which I’m sharing in the first part of the text below. While preparing for the trip and writing this note, I found the following resources extremely valuable: Jura Wine by Wink Lorch, The Sommelier's Atlas of Taste by Rajat Parr, Wine Science by Jamie Goode, and articles from the Children's Atlas of Wine. The second part of the text focuses on the details of my visit to Domaine Labet, including wine tasting notes.

A Quick Look at Jura's Geography

Located in Eastern France, Jura is positioned just 80 kilometers east of Burgundy's Côte Chalonnaise, extending towards the Jura mountain range, which borders Switzerland. Jura and Burgundy are separated by the Saône River valley, formed by tectonic forces that split a once unified geological region into two. Many wine writers find it helpful to compare Jura to Burgundy for visualization: like the Côte d'Or, Jura features an extended slope running from north to south. In a way, Jura kind of mirrors Burgundy: while the vineyards of Côte d'Or face southeast, catching the cool morning sun, Jura’s vineyards, situated on the western foothills of the Jura mountains, are mainly exposed to the southwest, promoting warmer afternoon sun. Both regions are dense with forests on their plateaus, have vineyards at an average elevation of 250-400 meters planted with Pinot Noir and Chardonnay as mainstay varieties, and predominantly consist of soil composed of clay and limestone (though in different proportions, which we will discuss below) as both areas were once covered by the sea millions of years ago.

But looking a bit deeper reveals definite differences between these two regions. Jura, with its similarly rich legacy, traditions, and abbeys near the vineyards, lacks the 'nobility' tag that has shaped Burgundy as a prestigious wine region. This makes Jura feel more authentic to my personal sensibilities. Compared to Burgundy, Jura wines remain quite affordable, despite rising demand driven by extreme popularity among Instagram hypebeasts in recent years. In fact, Jura has been under the radar for more than 20 years, favored by small communities who sought wines very different from those championed by Robert Parker (not to mention Japanese enthusiasts), and has historically maintained quite reasonable pricing if we look at it from this angle.

Production-wise, Jura was once a significant engine of French wine, with nearly 20,000 hectares under vine. However, due to a chain of challenges, Jura now remains a minuscule wine region with a vineyard surface area of about 2,000 hectares (in comparison, Côte d'Or has 8,000 hectares, and all of Burgundy nearly 30,000 hectares), accounting for less than 0.2% of France’s annual wine production, with up to 30% of it now being exported.

Yet, the wines of the Jura region are remarkably diverse, which I try to explain by three main reasons below, if you allow me some generalization.

Reason 1: Soil and Geology Puzzle

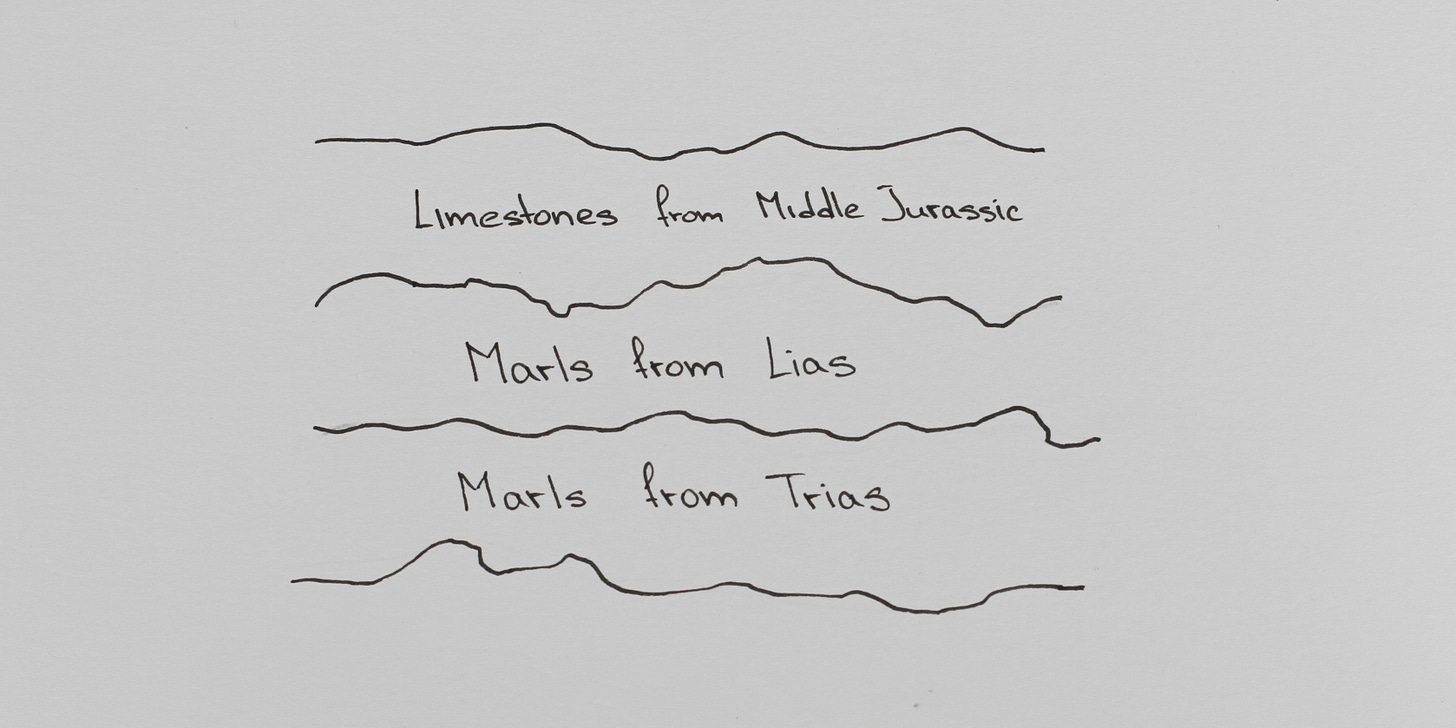

Beneath your feet lies a staggering complexity of soils, revealing the vineyards' profound geological diversity. Most of the soil is sedimentary, formed hundreds of millions of years ago at the bottom of a tropical sea. Imagine the soils of this part of France as a layered cake: on top is Bajocian limestone (just like in Burgundy), below is marl called Lias, and beneath that is a different type of marl called Trias. To be precise, marl, or marlstone, is a very fine-grained composition between fine-grained limestone and mudstone, impossible to differentiate visually, not a mixture of visible pieces of limestone interspersed with clay as is often misconceived.

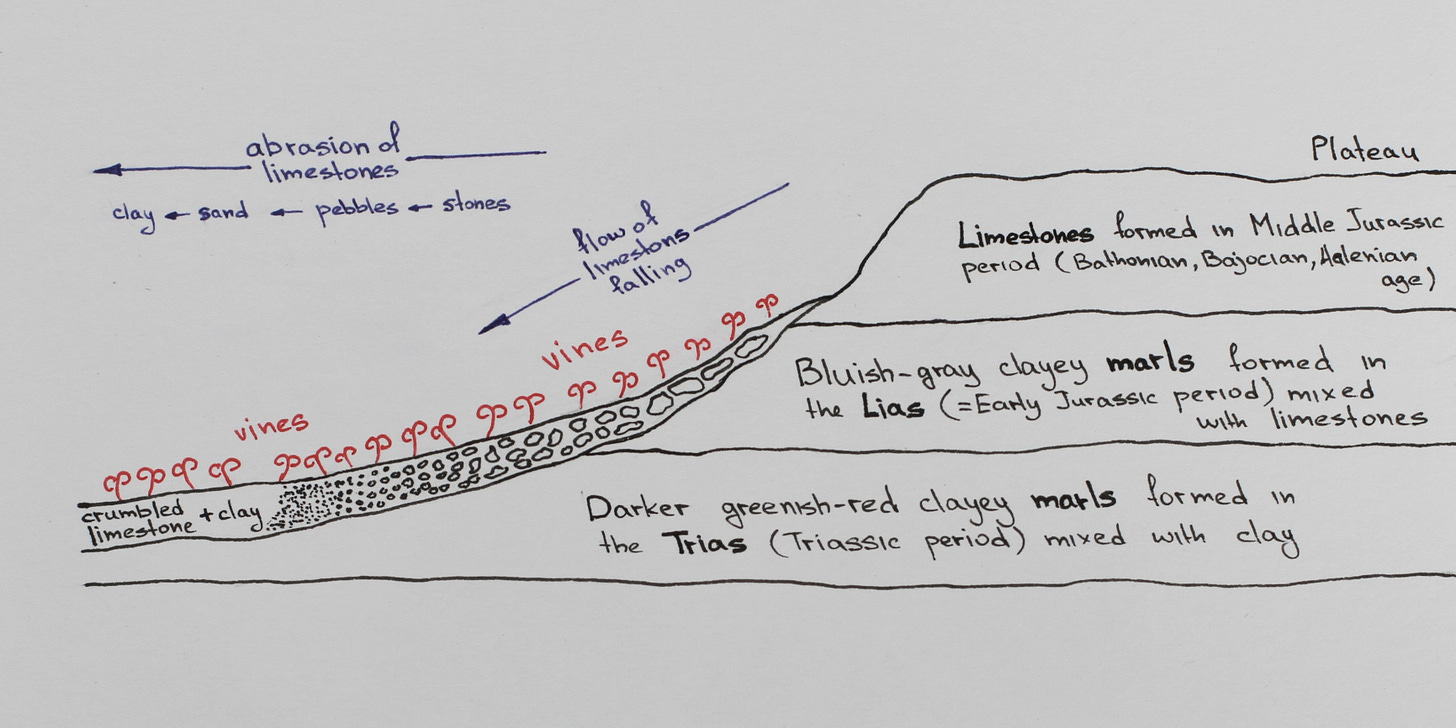

Now, let’s add a bit of complexity. Unlike the orderly stacked layers found in the Côte d'Or, the mountains beneath Jura twisted these layers on their side and pushed up the lower layers during the creation of the Alps. Imagine a layered cake that has tipped over in some parts. This geological activity formed plateaus (600 to 1000 meters), with slopes composed mainly of exposed marls and limestones. These slopes mark the beginning of the true elevations of the plateaus and are where Jura vineyards grow.

That’s why walking across just a few rows of vines in Jura might traverse tens of millions of years of geological time: from the Bathonian, Bajocian, and Aalenian age limestones formed in the Middle Jurassic period, to the older bluish-gray clayey marls formed in the Lias (a synonym for the Early Jurassic period), and even much older darker greenish-red clayey marl called Trias from the Triassic period. Burgundy has the same Lias and Trias marls, but they are buried under hundreds of feet of limestone.

To help digest this information, I found a very useful chronology of geologic periods illustrated here.

In general, clayey marls are found at the lower altitudes of slopes, while the majority of limestone remains higher up. Due to the geological activity described above, Jura vines predominantly grow on marl (about 80%), with the remaining 20% on limestone, a significant portion of which drops from plateaus to slopes and undergoes abrasion. In the Côte d'Or, the ratio between marl and limestone where vines grow is reversed.

This is a simplified overview, but the topic is endless. You can add much more detail and complexity. Just know that Jura's terrain is jumbled: there are blind valleys that twist and turn, outcroppings with star-shaped fossils, and even non-sedimentary rocks like metamorphic schist in some areas. This complex landscape explains why vintners like Labet bottle dozens of distinct cuvées, each differentiated by the specific geology beneath the vines.

Reason 2: Kaleidoscope of Grape Varieties

The region has remained rural and economically unstandardized, preserving its mixed agriculture by having grain and pasturage alongside vines. That's why a kaleidoscopic array of native grapes defines Jura today, without an exclusive focus on 'noble' varieties. Although Chardonnay plantings are now becoming more prevalent, old exceptions are still found everywhere: indigenous Poulsard (known as Ploussard in the village of Pupillin) and Trousseau (known as Bastardo in Spain and Portugal), along with Pinot Noir and the remarkable ancient Savagnin — progenitor of several of today’s world-beating grapes. Not to mention virtually extinct varieties like Béclan or Enfariné. Additionally, disease-resistant hybrids such as Rayon d’Or, Souvignier Gris, and many more are taking root in the minds of some vignerons, with Didier Grappe and Valentin Morel being the most vocal modern advocates.

Reason 3: Diversity in Wine Styles

Despite its tiny total production, Jura is marked by a remarkable diversity of wine styles, especially for white wines, which preserve local traditions while also integrating modern techniques. The wine styles that distinguish Jura today are not absolutely unique to the region, but some are archaic, having vanished from most areas that have evolved into commercially recognized regions. Let’s talk in detail about these styles.

Vin Jaune ("yellow wine"). This traditional Jura wine style, representing about 3.5% of the region’s wine production, is quite atypical to the modern palate. It must be made exclusively from the Savagnin grape and aged in oak barrels without topping for a minimum of 75 months before bottling, as mandated by law. The wine is aged in incompletely filled barrels in an often cooler and more humid cellar environment. This nurtures the formation of the voile or flor — a veil or biofilm primarily composed of Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, which grows on the surface of the aging wine. This yeast, although the same species responsible for alcoholic fermentation, is a specially adapted variant capable of thriving under the relatively hostile conditions inside a barrel. The air in the headspace at the top of the barrel contains oxygen, and the surface layer of flor yeast accesses this oxygen while simultaneously protecting the wine against oxidation and dramatically changing its character: the wine often remains fresh and pale in color, but the glycerol component is consumed by the yeasts which change the mouthfeel, making the wine less viscous, fresher, and bone-dry. There is also an increased level of a compound called sotolon, which adds specific nutty, spicy, curry notes to the wine profile.

Vin Jaunes from Domaine Labet (left) and Domaine Tissot, made from a single parcel, 'La Vasee' (right) Similar to Vin Jaune, wines using this technique can be found in other traditional regions, such as Jerez in Andalucía, the west coast of Sardinia, and Tokaj in Hungary. The yeast strains in these four regions that produce flor share a common ancestor from antiquity, originating from a fifth, unknown source. Whether or not voile appears is still somewhat mysterious. In regions where it isn't traditional, often the first flor-aged wines are made by accident: a layer of flor appears on the wine, and the winemaker might decide to take a risk and let it continue growing, making it a style choice. There now seems to be much wider interest in making wines this way, so you can start finding them all over the world.

Many white wines, including those made from Savagnin not classified as Vin Jaune, bypass the mandatory 75+ month barrel aging period without topping. This often occurs because the protective veil sometimes breaks or weakens as the wine ages in barrels, leading to oxidation. Consequently, winemakers may decide to bottle these wines after 24-36 months of flor aging, although the exact duration can vary. Alternatively, a winemaker might blend them with fresh or non-flor aged whites, including Chardonnay, and then bottle or further age the blend — combining oxidative and non-oxidative styles. A telltale sign on labels for these wines might include terms like Vin Non Ouillé ("wine without topping," indicating aging under flor in an oxidative style), Tradition, or Vin Sous Voile ("wine under veil"), if it involves a mix of oxidative and non-oxidative styles.

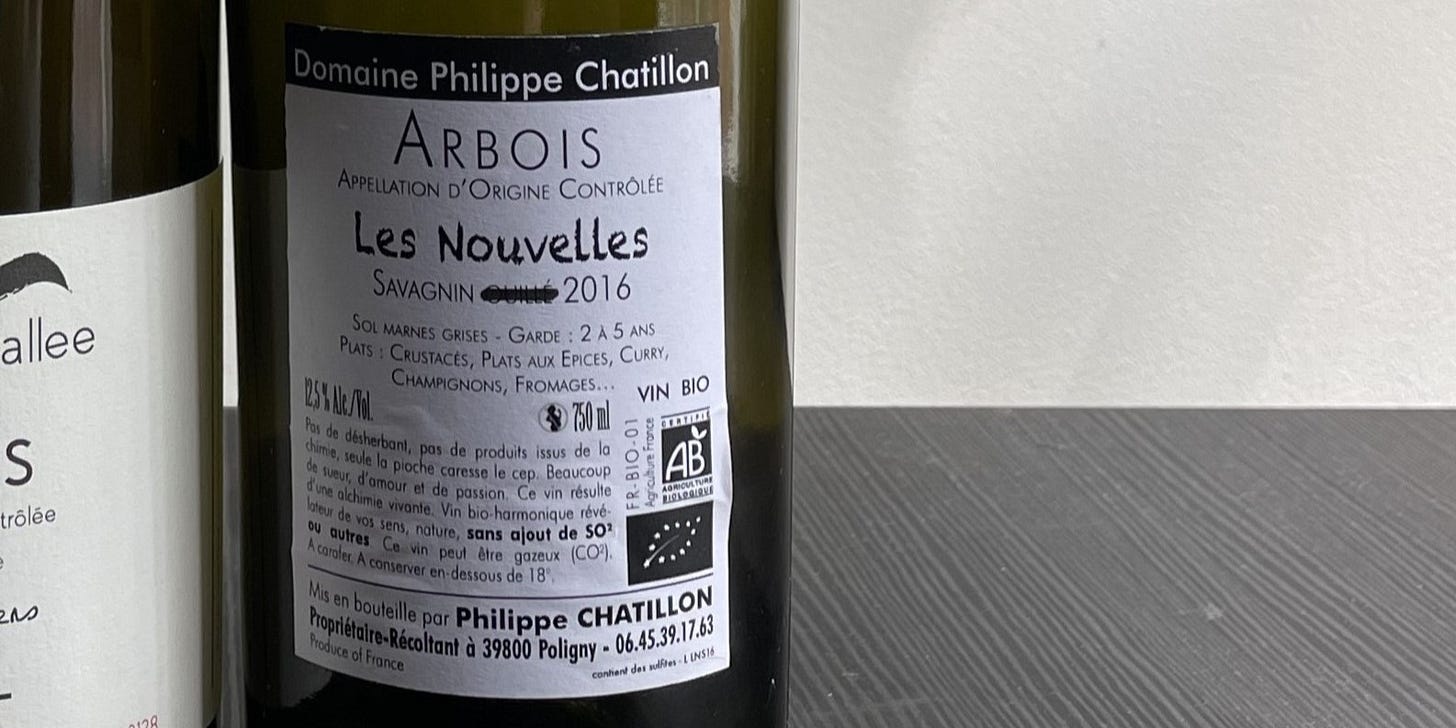

Nowadays, in Jura, it's not uncommon to find white wines produced in the contemporary style you’d expect — directly pressed, fermented, then aged in barrels with regular topping up to replace the liquid lost to evaporation, preventing any kind of oxidation. These wines, known for their specific barrel maintenance during aging that prevents the formation of a veil, are informally categorized under the term Vin Ouillé ("wine with topping"), a detail you can often find on the label. Historically not the most celebrated, the southern sub-region of Sud Revermont has now become renowned for its non-oxidative ouillé Savagnins and, especially, Chardonnays, although these wines are also found elsewhere in the region. These wines are typically lighter, fresher, and more precise than traditional whites.

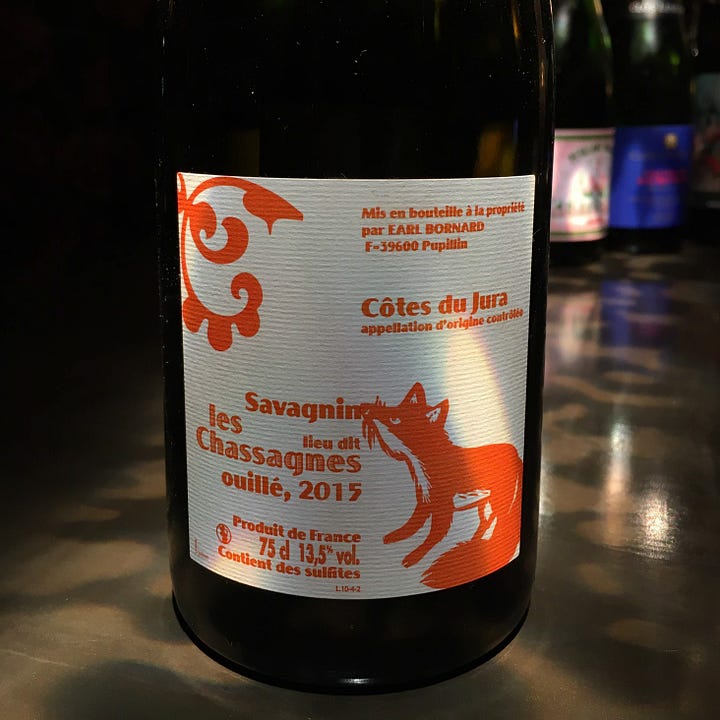

Les Chassagnes from Philippe Bornard and Cuvée Florine from Domaine Ganevat, both made with ouillé (in a non-oxidative style) To complete the discussion on wines made from white grapes, I should mention that skin-contact wines are also found in Jura, though they are quite limited in availability. These wines are usually indicated on the label as Maceration.

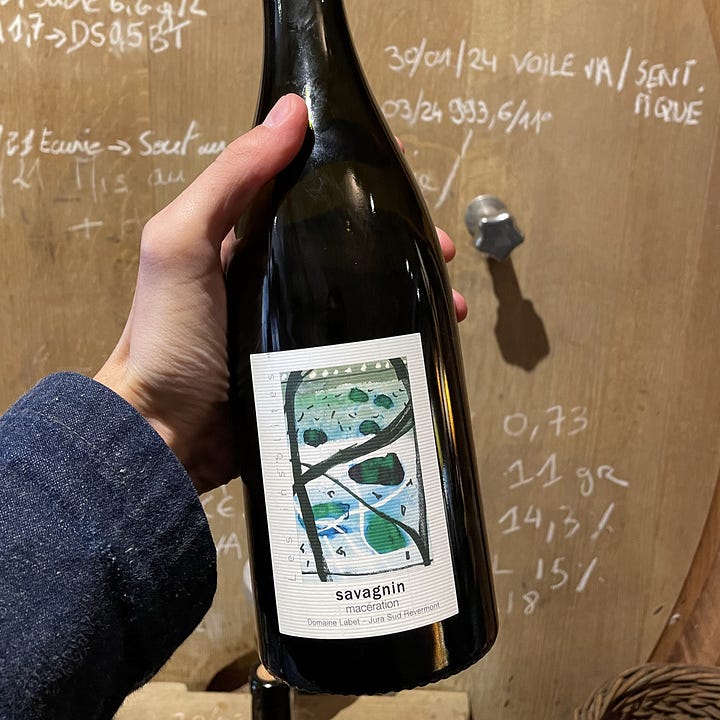

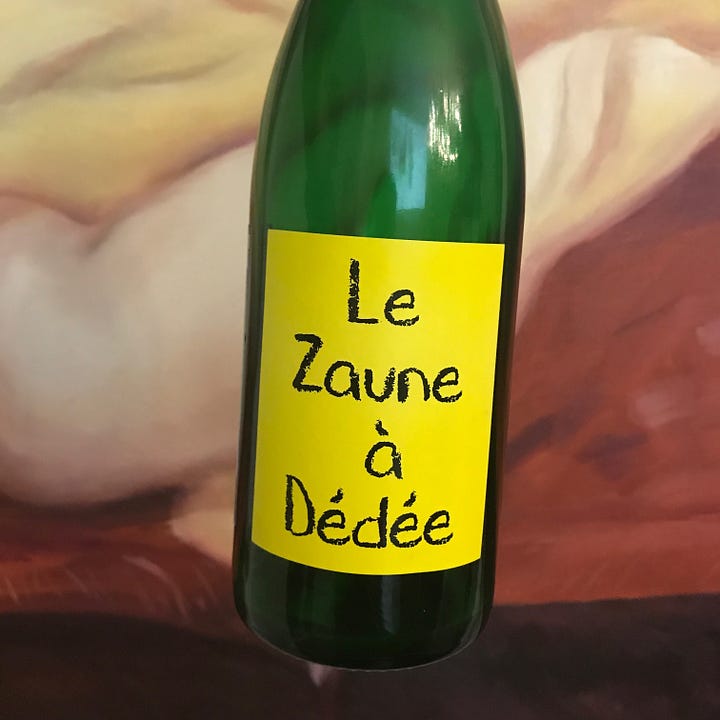

Savagnin Maceration from Domaine Labet with 10 days of skin-contact (left). Le Zaune à Dedee from Domaine Ganevat — an experimental blend of skin-contact Gewurztraminer and Savagnin aged for 7 years under a veil in barrel (right) Red wines in Jura are primarily made from Pinot Noir, Poulsard, or Trousseau, but also include Gamay and some virtually extinct local varieties like Enfariné (part of some Ganevat’s négociant labels) or Béclan (search for Amalgame by the Allante & Boulanger duo). Various techniques are employed in the production of reds, often including carbonic and semi-carbonic maceration. Generally speaking, Jura’s red wines tend to be lighter and more approachable than the whites right after bottling — which doesn’t mean they are any less desired and joyful, at least for me! This explains why locals always choose to drink the reds first before moving on to the whites.

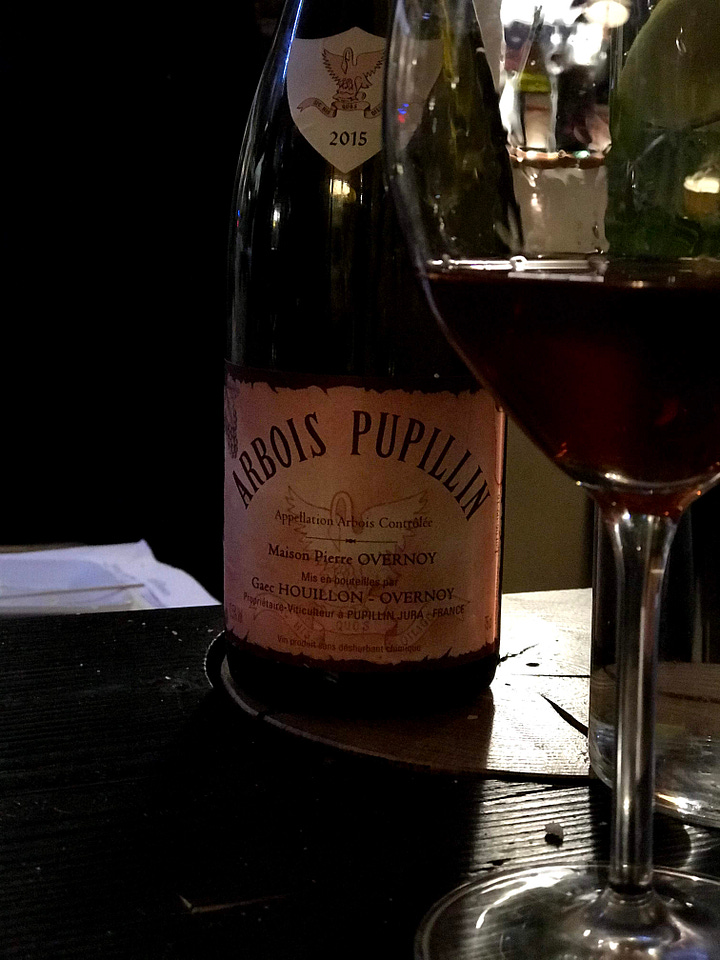

Poulsard from Pierre Overnoy (left). Declassified blend of Merlot and Chardonnay from l'Octavin (right) Vin de Paille ("straw wine"). These sweet wines, usually made from a blend of Chardonnay, Savagnin, and Poulsard (sometimes Trousseau), range from medium to very sweet and require a minimum of 14% alcohol and three years of aging, including 18 months in wood, by law. The grapes are picked early, dried for several months (traditionally in boxes with straw), and may develop noble rot. The pressing and fermentation processes are slow, and the resulting wines can vary in color and sweetness, with residual sugar levels ranging from 60g/l to about 130g/l. Some very traditional producers age the wines in oak without topping up, allowing them to gain some oxidative character. Additionally, some producers make similar sweet wines with lower alcohol content and higher residual sugar, or choose not to age the wine for the statutory length of time in oak, meaning the final wine must be sold under alternative designations on the label.

Macvin de Jura liqueur, by law, has to be made from the sweet juice and must of five permitted late-harvested grape varieties, reduced by half through boiling. The resulting liquid is usually not fermented but is then fortified with brandy until it reaches 16% alcohol, halting fermentation and leaving residual sugar. The liqueur is then placed in oak casks to age for six years. There is no fermentation process after fortification, and usually no fermentation at all. You can also find the indication Mistelle on the label.

Marc du Jura, or Eau de Vie de Marc ("water of life"), is a local pomace-based brandy with an alcohol content typically ranging between 45% and 60%.

Lastly, there is the sparkling wine (white or rosé) made using the traditional method under Crémant de Jura appellation rules. The production of Crémant de Jura is significantly growing nowadays, especially those based on Chardonnay as the main grape, which is boosting its planting. Besides Crémants, you can also find different variations of pét-nats in Jura.

Pét-Nat Tant Mieux from Philippe Bornard (left), and Crémant du Jura Rosé from Domaine Tissot (right)

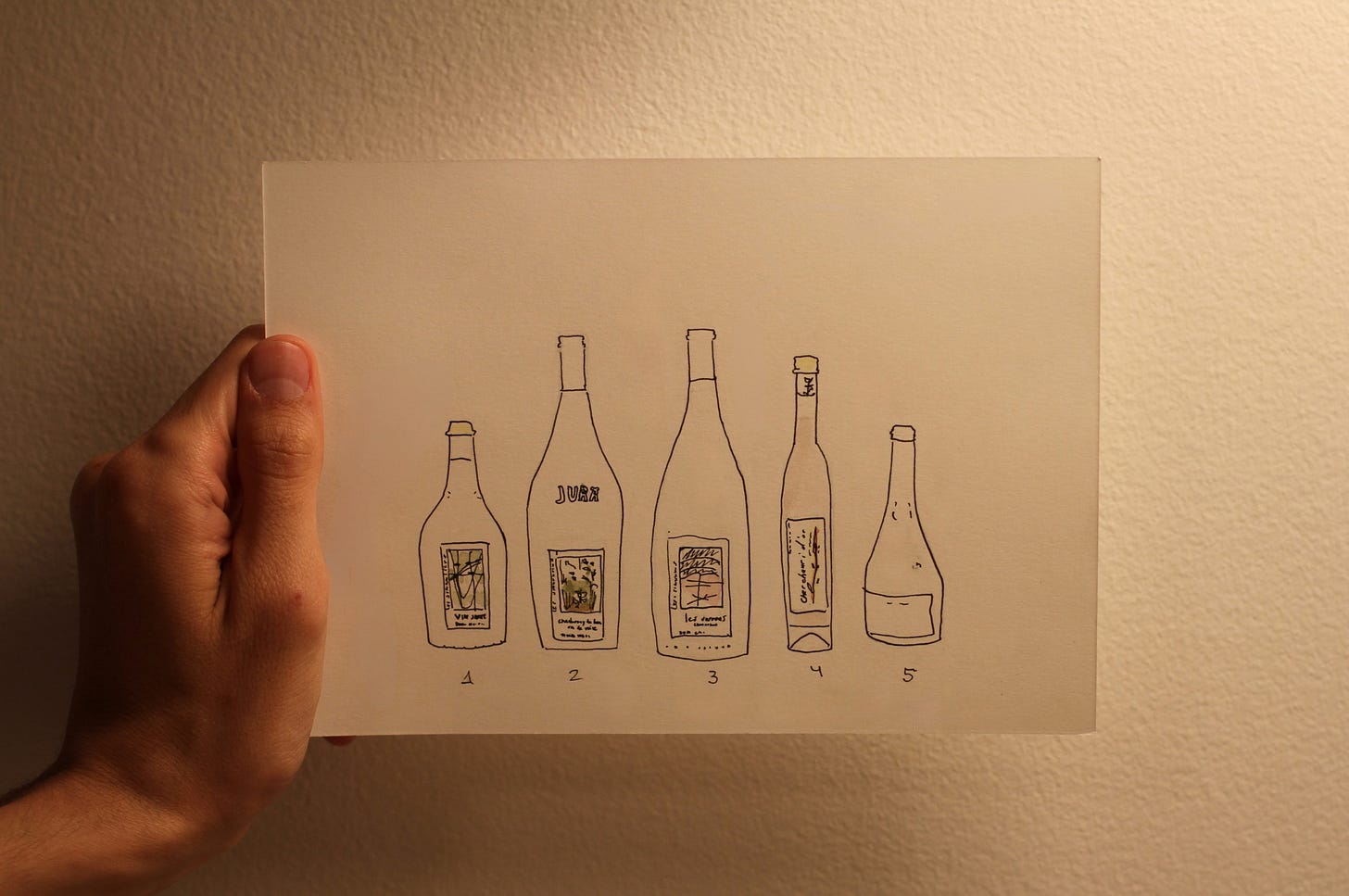

There are quite a few producers in Jura (including Labet) with a vast lineup of labels, making it easy to get lost in the complexity. To help navigate this, especially for white wines, there is a very simple bottle shape tip, which some producers follow (though not all), that can aid in initial high-level navigation. Check out the fantasy schema created by Alisa Olesova below.

Domaine Labet: Generational Passion and Excellence

Domaine Labet is located in the village of Rotalier in Sud Revermont, the southern sub-region of Jura. Along with its long-standing commitment to respectful viticulture, the domaine is famous for two groundbreaking practices in the region. The first, adopted in the late 1970s, was aging and bottling wine from individual parcels separately instead of the traditional blending from different vineyards. The second, developed in the late 1980s, was experimenting with vin ouillé ("wine with topping"), rather than aging wine under flor as was customary in Jura.

Both practices were pioneered by Alain Labet when he joined his father Jean Labet in the 1970s. Jean had founded the domaine as a polycultural farm devoted mainly to dairy cows in 1950. Alain began focusing more on viticulture, purchasing old vineyard sites from neighbors. Inspired by Burgundian wines, Alain, the father of the three siblings who currently run the domaine, sought to emphasize the distinct characteristics of each parcel, which he believed were masked by blending and traditional oxidative aging. His approach resulted in wines that are fresher, more precise, and reflective of the specific conditions of their vineyards.

Siblings Julien, Charline, and Romain have continued their father's vision, with an even greater focus on the detailed exploration of different parcels. Julien, the eldest of Alain’s three children, returned to the family domaine in the late 1990s after working at Domaine Ramonet and Hamilton Russell, aiming to further enhance the terroir expression in their wines. Being quite radical, he advocated for a shift towards organic viticulture, introduced Burgundy barrels alongside foudres, and progressively reduced sulphite levels.

Charline and Romain joined the team a few years later. There was an informal split between the siblings: Julien was primarily responsible for wines made in a non-oxidative style, Charline focused on oxidative styles, and Romain dedicated himself mostly to vineyard work. Alain retired in 2012, giving full control to his children but still helping out whenever he wanted.

The domaine owns around 13 hectares spread over 45 parcels, with the majority of vines being old massal selections between 50 and 100 years old. The family considers vines under 40 years old as young. Their thorough focus on each vineyard's specifics results in a tapestry of up to 20 terroirs that might be bottled separately — such cuvées include the plot name on the label. Depending on the year's conditions and the intended wine style, wines might be made from single parcels or blended from parcels within the same area. This approach contributes to Labet's diverse range of labels, which can vary slightly from year to year.

Before my current visit, I had never seen the old domaine label. The modern, eye-catching designs are a legacy of the siblings' influence. While the diversity of the wine range might seem complex, each bottle is an ode to the transparency of meticulous terroir detailing and winemaking techniques, with full information provided on the back.

The family works with all common Jura grape varieties. Whites are made in both non-oxidative and traditional oxidative styles, including vin jaune. They are vinified and aged in old Burgundy barrels, demi-muids, and foudres for 18 months or longer if needed (sometimes up to 36 months). Reds undergo cold pre-maceration, where the grape clusters are left in refrigeration for 5-10 days to enhance fruitiness through low-temperature maceration inside the berries. Red grapes are usually destemmed and then aged in barrels or foudres for a shorter time than whites. Fermentation typically takes place in fiberglass, concrete, or foudres. Amphoras and concrete eggs are also used for some cuvées, such as macerated Savagnin. Additionally, the domaine produces Crémant and a full spectrum of special beverages, including sweet “straw wine” (declassified Vin de Paille), fortified Macvin de Jura, and Eau de Vie de Marc.

There is minimal to no intervention during vinification. The family holds the view that the natural yeast populations on each vine are an integral part of the overall terroir, so they advocate for spontaneous fermentation only. The first vintages made without SO2 were in 2008-2009. Nowadays, they rarely add 1-1.5 mg of SO2 per 100 liters to block malolactic fermentation if it starts during alcoholic fermentation. The idea behind this is to make the lactic acid bacteria responsible for malolactic fermentation dormant, protecting the wine from potential excessive volatile acidity (a byproduct of bacteria consuming sugar). This risk arises when malolactic fermentation begins during alcoholic fermentation when sugar levels in the must are still high, and the bacteria compete with yeasts for unfermented sugars, which greatly increases the potential for acetic acid production.

The deep knowledge of each plot and the meticulous approach to winemaking left a strong impression on me, highlighting that the brilliance of the final product is the result of constant hard work. At one point, when we were asking detailed questions about the vinification of one of the wines, Charline brought out an A4 paper filled on both sides with small handwritten notes about that specific cuvée and vintage. It covered everything from the weather that year to every vinification detail.

By the end of our three-hour visit, it felt like only 15 minutes had passed because it was so enjoyable. The fact that the siblings have lived and worked together as a close-knit family for so many years, combined with the overall warmth and genuine simplicity with which we were welcomed, genuinely touched me and left me wishing to come back one day.

We were tasting the 2023 vintage directly from the vessels, mostly reds. The vintage was generous production-wise, with even an overproduction of grapes, so the harvest was split into several batches, up to three. The rest of the wines we tried were bottled ones, mostly from 2022 and 2021. The 2022 vintage was good, with an average yield of 55 hl/ha, except for Poulsard, which had a much lower yield. The 2021 vintage was extremely challenging, with up to 90% loss, resulting in limited wine availability.

Trying to generalize the style, I can say that the wines are energetic, precise, and layered. They are very clean but far from being sterile. You'll hardly find a bottle with pronounced flaws like excessive volatile acidity, reduction, or oxidation. However, the wines might have the subtlest touch of these components, which adds to their vibrant character and helps their beauty fully express itself — something I enjoy and look for in wine. All the wines speak of their place, and yes, they are delicious.

Reds are light, crunchy, and ready to drink young. They offer amazing drinkability and complexity, and I absolutely love them. The benchmark domaine wines — non-oxidative whites — are structured and complex, with electric acidity. They are best stored for a few years to become more generous and less laser-sharp. Non-topped whites are noble and opulent, showing interesting oxidation results with an almost sweet taste, reminiscent of roasted nuts. These wines are so joyful and special that I’m ready to buy them at any price, though they are produced in very low quantities, with many going directly to the family cellar. Vin jaunes are complex and among the most delicate, enjoyable upon release and immortal for aging.

Below are some brief wine notes from the visit.

Trousseau 2023, unbottled

Light in color. Juicy and light with a slight bitterness in the aftertaste. Mouthwatering.

Young vines of Trousseau à la Dame planted in 2016. A blend of three parcels from the neighboring communes of Grusse, Rotalier, and Vercia, planted on red clay over Bajocian limestone bedrock.

Trousseau 2023, second pass (selection of less compact berries), unbottled

Slightly deeper in color. Sweeter, peony floral, strawberry and ripe cherry on ice. Sweeter taste with a warmer finish.

Will likely be blended with the previous wine before being bottled.

Les Varrons Pinot Noir Sélection Massale 2023, unbottled

Reductive opening. Red berries and cherry-driven. Zesty, deeper than Trousseau, yet fresh.

Low yields from a tiny 0.25-hectare parcel, planted massal in 1983 on red clay over Bajocian limestone bedrock.

En Billat Poulsard 2023, unbottled

Tea, red berries, and herbs with slightly coppery notes. Subtle and possibly my favorite red.

0.31 hectares parcel of massale Poulsard planted in 1988 on an east-facing slope with clay and schist (schistes-carton) from the Lias period.

Les Varrons Pinot Noir Sélection Сlonale 2023, unbottled

Reductive opening. Sweet tea, slightly yeasty, with a spicy finish. Unfinished yet.

Clonal selection of Pinot Noir planted in 1985 and 1986 on red clay over Bajocian limestone bedrock.

Les Varrons Pinot Noir 2022

Reductive opening. Darker, denser, with more pronounced tannins than the 2023. Nice fruit sweetness.

La Reine Cepage Rouge Gamay 2022

An aromatic delight. Extractive (for Labet). Red berries, pepper spices, and a hint of oak. Ideal balance of sweetness and acidity. Interestingly, Gamay has more structure and a serious vibe compared to all of Labet's other reds, and it ages wonderfully.

0.28 hectares of young vines planted in 2016, and 0.12 hectares of massale old vines planted in 1963, growing on clay-silt soil with a Bathonian limestone base.

Metis 2023, unbottled

Meaty and sappy. Like Gamay, fuller-bodied than the other reds.

The varietal blend for this label differs year to year. In 2023, it is 50% hybrids, with the rest being Gamay and Trousseau from mixed parcels and terroirs.

En Chalasse Savagnin 2021

Nice reductive-touch opening. Pure mineral notes with salty lemons, orchard fruits, and a light buttery touch. Malic-kind of acidity (vintage specific). Long persistence. Delicious.

Savagnin jaune and vert from vineyards planted in 1989 and 2003, growing in the bluish-gray clayey marls of Lias.

La Pellerine Chardonnay 2021

Buttery, very acidic, and salty. Packed with flavor. Immense. Needs time to open fully.

If there is only a small quantity of this wine aged in the vessel, it usually develops flor. Vines planted in 1977 and 1986 on a north/east-facing slope with marl soils from the Lias period and Bathonian limestone base.

Lias Chardonnay 2021

Pears, white peach, sage, and slight creaminess giving an airy texture effect. Beautiful salinity, density, and concentration. Long and delightful.

Blend from three parcels (Le Cret, La Bardette, La Reine) planted from 1975 to 2017 on marl soils from the Lias period on a Bathonian limestone base.

Les Varrons Chardonnay 2021

Overall, this wine has seemingly less concentration and opulence compared to Lias Chardonnay. A touch more vanilla in the aroma. Pingy citrus notes. Electric, nervy acidity. Needs some aging.

Massal selection plot planted in 1932 and 1940 in ochre-colored clay over Bajocian limestone on a mid-slope facing east.

Macération Savagnin 2022

Ripe pears, tangerine zest, juniper, honey, and a light note of roasted hazelnut. Ripe, slightly sweet, but fresh and well-mannered.

Savagnin jaune planted in 1991 and 1993 on blue marl soils from the Lias period. 36% destemmed, the rest is whole clusters. Pressed and quickly transferred to amphora for 10 days of maceration. Aged in amphora (59%) and in a 6 hl concrete egg (41%).

Cuvée du Hasard Chardonnay 2015

Aromas of apple, candied citrus, fennel, iodine, curry, and a mix of wet almond and roasted sweet hazelnut. Rich textured mouthfeel with beautiful sweetness, pronounced acidity and salinity, and a nice touch of bitterness. So intense, layered, and balanced. An absolute stunner.

Chardonnay massale from two parcels of 65-year-old vines. Aged for over six years in barrels, four of those under a veil. Blended from different barrels prior to bottling. This 2015 vintage was bottled in June 2022. Produced in rare vintages and mostly kept in the family's personal cellar. It's a wine you buy on sight, regardless of the price.

Vin Jaune 2015

Citrus freshness with a soul of sea breeze. Fresh and easy to drink, with sublime balance. This is the supreme Vin Jaune for me.

A blend of Savagnin jaune (62%) and vert (38%) from different parcels — Charriere, Billat, and Cret — planted between 1945 and 1975 on marl from the Lias period. Aged for 7 years in barrels under a veil.

Vin Jaune 2016

Sweeter on the nose with notes of roasted nuts and halva, complemented by pungent salinity. Nervy acidity. Needs some time to settle.

A blend of Savagnin jaune (60%) and vert (40%) from different parcels — Chalasse and Charriere — planted between 1989 and 2003 on marl from the Lias period. Aged for 6 years in barrels under a veil.

Les Chercheurs d'Or 2009

Toffee, coffee, and overripe, melting apricots, with a touch of waxiness. Fresh acidity, rich and viscous texture. Absolutely delicious.

A blend of Chardonnay, Savagnin, and Poulsard from old vines. The grape bunches are laid on a straw bed in wooden boxes for 4.5 months until they develop raisin-like intensity. Pressed in late February, then aged in barrels for 8 years and an additional 6 years in the bottle. Charline mentioned that using natural yeasts resulted in 8% natural alcohol and a much higher concentration of sugars (148 g/l) than the norm, which is why this wine did not meet the AOC criteria for vin de paille (minimum 14% alcohol) and was released as declassified.

Jura, Rotalier, April 2024

🩷 what a wonderful dive in